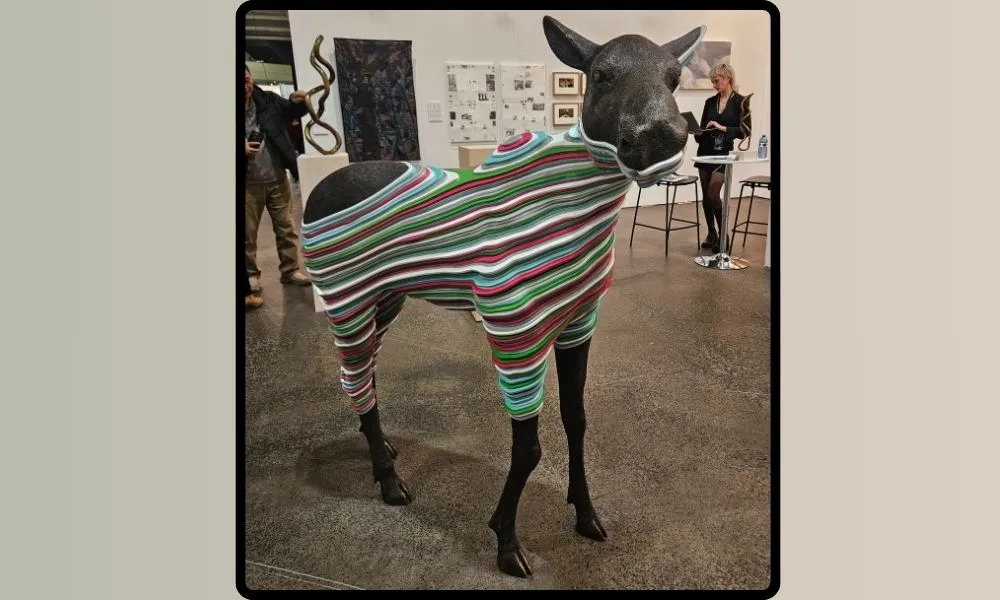

This past weekend, I attended the annual Toronto Art exhibition, hosted at the Toronto Metro Convention Center, which also happens to be one of the most sustainable and energy efficient event spaces in the City. Metro Toronto Convention Centre is always fun, and is a fantastic reminder of how powerful originality can be.

As I walked through the galleries, I couldn’t help remembering a litigation case I worked on which intertwined art, forgery, and fraud. Some of you may be aware of an artist named Keith Hering, prominent in the 80s for his pop-art style. Hering passed away in 1990, but his art continues to attract attention. In 2020, Coach ran a successful collaboration campaign using Haring’s Mickey Mouse on its bags. My story isn’t anything grand like the Coach limited edition run, but it is a story that can happen to anyone, and especially to those who love art.

In my case, my clients had loaned a significant amount of money, in a number of instalments, to a person who provided her collection of Haring artworks as collateral. On paper, it looked like a safe transaction: the artworks were by well-known artists whose work is known to have significant value. Certainly, the collection was worth more than the loan. Or so it appeared. During the process of the litigation, it became known that the works were actually contested by the Keith Haring Foundation as fakes. They could not be moved or sold during the course of those proceedings. The Foundation sued the owner for trademark infringement and dilution, copyright infringement, false advertising as well as cybersquatting. The Foundation has the power to authenticate the artworks, and has deemed them to be forgeries.

In my clients’ case, the loan was never repaid, which is how they became plaintiffs in a litigation for breach of contract and fraud. My clients could have attempted to seize the paintings, which as collateral was within their rights to do. But to what end? Forgeries are never worth the value of the original, and in most cases cannot be legally sold, or displayed as originals.

This case became a lesson in how fragile “value” can be when it depends on authenticity.

.webp)

In art transactions, provenance — the documented history of a work’s ownership — is everything. Yet it can also be easily manipulated. A forged certificate or a convincing backstory can mislead even seasoned collectors and lenders.

From a legal standpoint, the key question often becomes: Who bears the risk of inauthenticity? If the loan agreement lacks robust warranties or authentication clauses, lenders may find themselves with little recourse beyond suing for fraud — a much harder case to prove.

Art-backed lending is a growing niche in finance, but it carries unique risks. Lenders need more than an appraisal — they need verification.

Courts have shown limited sympathy for parties who rely solely on an owner’s word or reputation when millions are at stake.

Litigating over forged art introduces its own challenges. Expert testimony often becomes the centerpiece — with one side’s specialist affirming the work’s authenticity and the other’s dismantling it. These cases can hinge on nuanced questions of brushstroke patterns, pigment analysis, and forensic imaging — far removed from typical commercial disputes.

Beyond the technicalities, they raise a philosophical question: if value lies in belief, what happens when that belief dissolves?

For lawyers, lenders, and collectors alike, the lesson is clear: art is a beautiful asset — but a risky one. In every transaction involving artworks, provenance must be treated as evidence before it becomes evidence in court.

What happened to my clients? They got judgement against the defendant the full amount of the loan, and the artworks were discarded as viable collateral.

__

Anna practices corporate litigation and business law in Toronto, with a specialty in entertainment law.